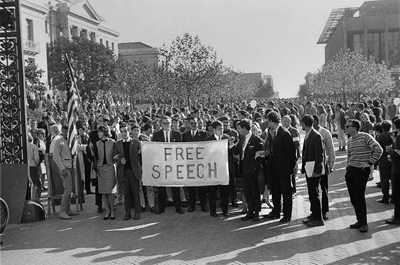

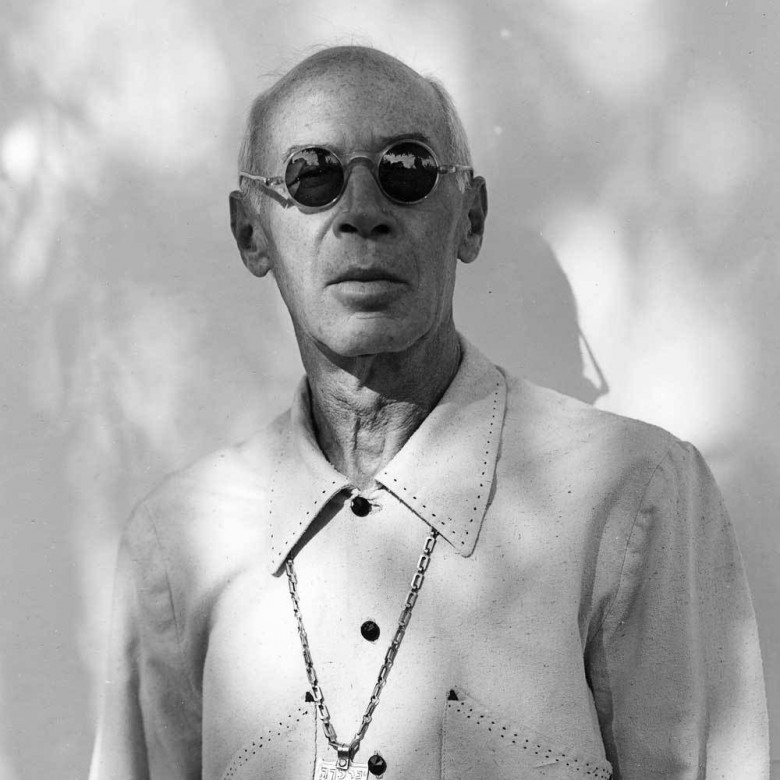

Cheyanne Gustason wrote a wonderful review of Ping-Pong 2014 for this issue of NewPages. This issue of Ping-Pong focused on Free speech as we celebrated the 50th anniversary of the free speech trial of Henry Miller’s book, Tropic of Cancer.

Ping•Pong

2014

Annual

Review by Cheyanne Gustason

If you have ever visited the Henry Miller Library in Big Sur, California, you likely noticed a ping-pong table. This table, nestled amidst towering redwood trees, brings the library’s many visitors together in a single place, with a single purpose: ping-pong. It is appropriate, then, that the Library’s literary journal, Ping•Pong, unites a wide array of voices and works in a single volume, and to common purpose.

The 2014 issue of Ping•Pong centers on topics of freedom and censorship, themes central to the life and legacy of Henry Miller himself. Editor-in-Chief Maria Garcia Teutsch begins her opening letter with the statement, “speech is not free, someone has paid the tab for you.” (iii) While the journal contains a variety of poems, artwork, short stories, and more, there runs throughout its pages an appreciation of those who paid the tab and paved the way.

Some of this appreciation is obvious, like the discussion and inclusion of works by Russian poets including Anna Akhmatova and Vladimir Mayakovsky, who were mercilessly persecuted in early 20th century Russia. Works by these two, and some of their peers, have been translated into English included in this issue of Ping•Pong. These pieces, surrounded by modern works, raise questions about the nature of censorship and its cost, to both individuals and society. Many of the translated Russian pieces have a surreal slant, which makes it all the more biting when they depict cruelties and violent ironies that are all too real. In an excerpt from “Wild Honey Is a Smell of Freedom,” Akhmatova writes “Wild honey has a scent – of freedom [. . .] But we have learned that// blood smells only of blood.” (100) Written in Leningrad in 1934, one can hear the echoes of revolution, of strong spirits and stronger institutions, and the realities of censorship and the importance of the creative voice are made all the more resoundingly clear.

The issue is not all heavy-handed. Quite the contrary. There are many pieces that are not only thought-provoking, but artfully elicit smiles and laughter, both bitter and mirthful, as well. Yet even these lighter pieces explore themes of censorship and material that might be condemned if not for our forefathers of free speech. Jeanine Deibel’s poem “A-Team: Swinging the Lead” is a delightful trip through the possibilities of alliteration. Some favorite lines: “My power animal is an antelope/ I worship Angus idols/I curse in my alphabet soup.” (36) Even this- to curse in alphabet soup, is that not a subversion of a comfortable classic? Is such subversion necessary, imperative, even just plausible, to bolster artistic freedom? Throughout Ping•Pong, even moments of levity harbor serious and thought-provoking undercurrents.

Resting at the end of the issue is an interview with poet Alice Notley. It is a fitting finale, as Notley discusses many themes pertinent to the other works and the issue in general. She mentions her work with Allen Ginsberg, who was no stranger to issues of censorship and artistic freedom. She discusses her process, sharing her work (or not), and differences between France, the United States, and Germany in both language and acceptance. At one point she claims, “Sometime [sic] I suspect the French of not liking poetry at all.” (196)

Ping•Pong is host to many styles of writing and expression, and a wide array of authors, which makes it a dynamic petri dish of creativity (and a lot of fun to read). Some pieces brought tears to my eyes (I won’t say which, you’ll have to guess). Others had me shaking my head, or my fist, at either the content, or the way it would once have been (or still might be) suppressed. There is humanity, beauty, heartbreak, and elation, as well as (sometimes disturbing) profanity, sexuality, and violence; and all have a voice in the poems and fiction seen here. The art included in this issue is also intriguing and thought provoking, fitting nicely with the themes and emotions displayed in the written pieces. In fact, I would look forward to seeing a bit more visual art included in Ping•Pong’s next issue.

Appropriately, this year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the Supreme Court decision that made Henry Miller’s classic Tropic of Cancer legal to read and sell in the United States. While Miller’s persecution may not have equaled that of writers like Ahkmatova and Mayakovsky, it is also not so long ago that Miller’s work was verboten in our “land of the free.” Ping•Pong, much like the library that publishes it, perpetuates the legacy of Henry Miller’s work, which includes the freedom of all writers and artists to be seen and heard. This edition of the journal explores and expands on these themes, making it not only an enjoyable read, but an important one as well.

Originally published on NewPages here.

Henry Miller Memorial Library blog here.

Author Bio:

Cheyanne Gustason is a writer and artist living in Los Angeles, California. She has written for Backstage Magazine and is currently working on her first children’s book. She has Bachelor of Arts degrees in Film & Media Studies and History, and recently earned a Juris Doctor.